A Proper Vintage Store

Welcome to Any Old Vintage

The award-winning Any Old Lights has grown! While still selling stunning vintage lighting, we also now work with experts in the fields of vintage clothing, homeware, entertainment collectibles, books and LPs, to bring you the full 360˚ vintage experience. Same ethos: friendly customer service and a magpie-eye on classic high quality.

Browse Our Store

Tripods

Very limited stock available. Extremely hard to find these - if at all - here in the UK.

-

Exclusive Adjustable Steel Tripod

Regular price £225.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

Exclusive Adjustable Heavy Teak Surveyor's Tripod

Regular price £275.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

Exclusive Adjustable Classic Teak Tripod

Regular price £100.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per£150.00 GBPSale price £100.00 GBPSale

-

Vintage & Retro Wall Lights

Retro and vintage nautical and industrial wall lights, including bulkhead lights and...

-

Vintage & Retro Ceiling Lights

Vintage and retro ceiling lights, in nautical and industrial designs, including rare...

-

Vintage Tripod Lamps

These stunning vintage floor lamps are all custom-created in our workshop, pairing...

-

Vintage Table Lamps

Vintage & retro desk and table lamps, including our exclusive budget "lighthouse"...

-

Vintage Clocks

Our highly collectible vintage wall clocks have been salvaged from decommissioned ships...

-

Maritime Antiques

Through our Any Old Lights contacts, we offer a selection of rare...

-

Vintage Clothing

We cherrypick only the highest quality vintage and pre-loved clothing, by respected...

-

Vintage Accessories

Hats, bags, shoes, sunglasses... We track down only the funkiest vintage accessories...

-

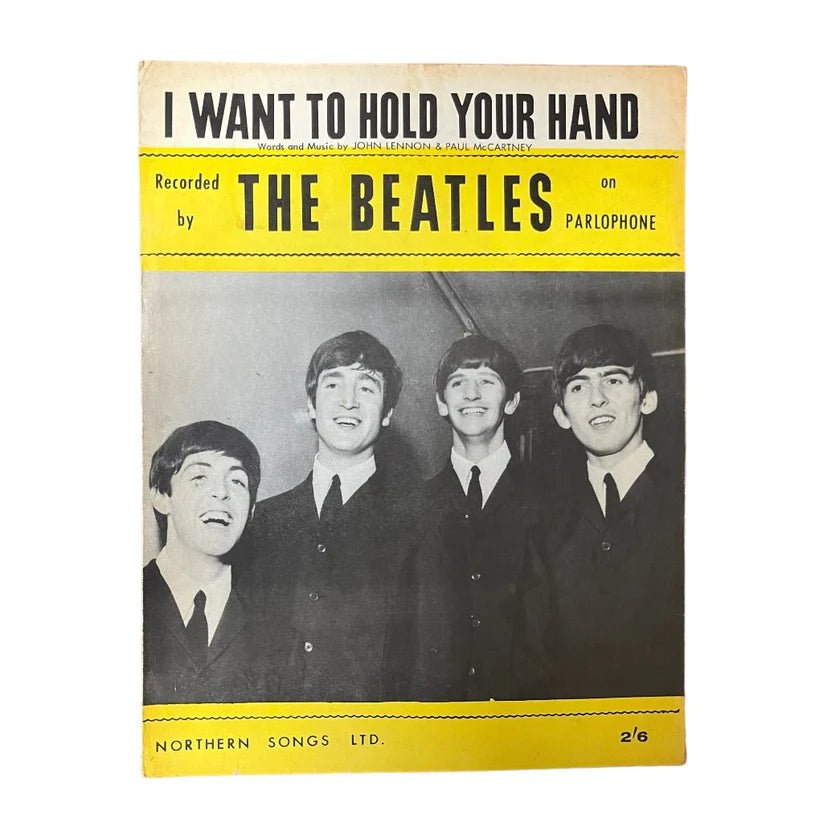

Vintage Collectibles

Our Aladdin's cave of vintage and antique collectibles features anything from rare...

-

Vintage Books, Mags & Sheet Music

Here you'll find old books, from Penguin Classics to antique guidebooks, and...

-

Vintage Paintings, Prints & Posters

Our carefully curated vintage art selection features classic movie posters, antique oil...

-

Vintage Model Kits & Toys

If memories of Airfix and Tamiya kits make your heart sing, or...

We're based in Cornwall

Any Old Vintage opened in late June 2023, at 14 Lostwithiel Street, in Fowey, Cornwall. There you can browse our full range of vintage and retro. This website features all of our lighting, clocks and maritime antiques, and a selection of our other items. Do contact us with any queries or if you're after something specific.

We have also started adding our stock to the Vinted app - a gradual process!

Get in First!

Our vintage stock moves fast and we're always finding new gems, so this website is being constantly updated (with a sizeable backlog 😬). Join our First Dibs club to receive a weekly email featuring the pick of our latest items, plus free UK shipping offer. Unsubscribe at any time.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.